A detailed explanation of the usage scenarios, principles, and best practices of TypeScript double assertion (as unknown as), comparing differences with as any. Learn how to avoid type errors while maintaining type safety, with real project cases and pitfall avoidance guides.

As a developer with years of experience in TypeScript projects, I’m sure many of you have encountered this dilemma: While TypeScript’s strict type checking effectively prevents numerous bugs in advance, you’ll often face situations where the compiler is “rigid” when integrating third-party libraries, handling complex DOM operations, or refactoring legacy projects. You clearly know the specific type of a value, but the compiler can’t infer it—this is where type assertion comes into play.

When it comes to type assertion, the first thing that comes to mind is as any. But seasoned developers know that as any is like a “master key” that bypasses all type checks entirely, essentially abandoning TypeScript’s core advantage and potentially laying hidden pitfalls for the future. Is there a solution that can complete type conversion while retaining as much type safety as possible? The answer is the as unknown as double assertion.

In this article, I’ll comprehensively break down as unknown as from basic principles and usage scenarios to real-world cases and pitfall avoidance guides, helping you truly understand and use it correctly instead of copying it blindly.

I. First, Grasp the Basics: What is the unknown Type?

To understand double assertion, you first need to clarify the nature of the unknown type. Many people confuse unknown with any, even thinking they are “more or less the same thing,” but in reality, their design purposes are completely different.

To summarize in plain language:

any: “I don’t know what type this is, but it can do anything”—completely disables type checking. You can call any method or access any property on it, and the compiler won’t report an error.unknown: “I don’t know what type this is, but it can’t do anything”—also an “unknown type,” but the compiler imposes strict restrictions on operations. You can’t modify or call it in any way until you explicitly define its specific type.

Here’s an intuitive example to illustrate the difference:

// any type: No type checking at all

let anyValue: any = "hello world";

anyValue.toUpperCase(); // No error

anyValue.foo(); // No error (runtime error occurs only if foo doesn't exist)

anyValue = 123; // No error, can be assigned freely

// unknown type: Strict operation restrictions

let unknownValue: unknown = "hello world";

unknownValue.toUpperCase(); // Error! Compiler disallows direct method calls

unknownValue = 123; // No error, unknown can accept any type of value

// Must clarify the type before operation

if (typeof unknownValue === "string") {unknownValue.toUpperCase(); // Compiler infers string type here, no error

}From this example, you can see that unknown is a “safer version of any”—it can also represent any type, but retains a “bottom line” of type checking, preventing you from operating on values arbitrarily. This is the core reason it can serve as an intermediate bridge for double assertion.

II. Recap the Basics: The Nature of TypeScript Type Assertion

Before delving into double assertion, let’s recap the core role of TypeScript Type Assertion. Simply put, type assertion is a way to “tell the compiler that you understand the type of a value better than it does.”

When the compiler cannot infer the specific type of a value from the code context, you can explicitly tell it via assertion, thereby unlocking corresponding type operations. The most common scenario is DOM element manipulation, for example:

// document.getElementById returns HTMLElement | null type

const element = document.getElementById('user-input');

if (element) {

// We know this is an input field, so assert as HTMLInputElement

const inputElement = element as HTMLInputElement;

console.log(inputElement.value); // Can safely access value property now

}Here, as HTMLInputElement is a typical single assertion—sinceHTMLElement is the parent type of HTMLInputElement (a subtype contains all properties and methods of its parent type), this assertion is safe and complies with TypeScript’s type system rules.

A key point about “subtypes and parent types” that many beginners easily stumble on:

If type S is a subtype of type T, it means S has all the properties and methods of T, plus possibly additional properties of its own. In this case, a variable of type S can be safely assigned to a variable of type T—this is because the object of type S contains all the information required by type T. This aligns with the Liskov Substitution Principle, which states that subtypes should be substitutable for their base types.

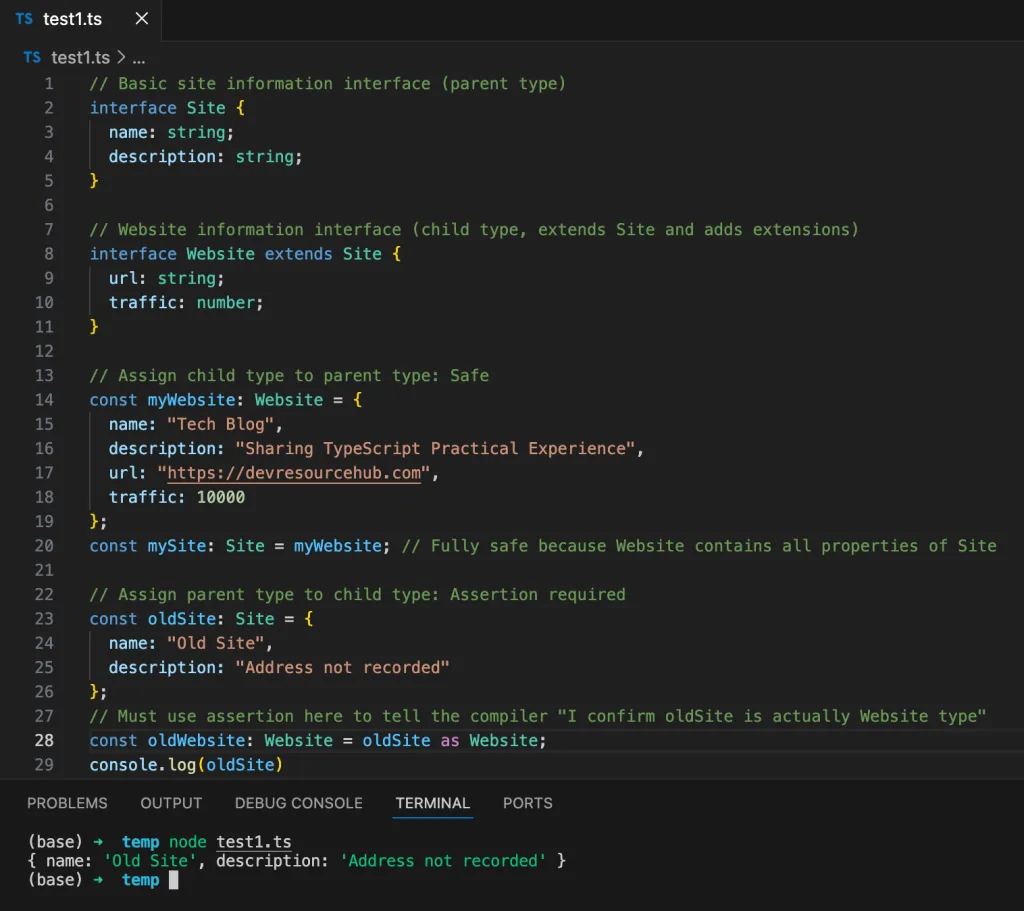

Here’s an example of interfaces commonly seen in real projects:

// Basic site information interface (parent type)

interface Site {

name: string;

description: string;

}

// Website information interface (child type, extends Site and adds extensions)

interface Website extends Site {

url: string;

traffic: number;

}

// Assign child type to parent type: Safe

const myWebsite: Website = {

name: "Tech Blog",

description: "Sharing TypeScript Practical Experience",

url: "https://devresourcehub.com",

traffic: 10000

};

const mySite: Site = myWebsite; // Fully safe because Website contains all properties of Site

// Assign parent type to child type: Assertion required

const oldSite: Site = {

name: "Old Site",

description: "Address not recorded"

};

// Must use assertion here to tell the compiler "I confirm oldSite is actually Website type"

const oldWebsite: Website = oldSite as Website;

This kind of “parent type → subtype” assertion is a common scenario for single assertion and is also safe—provided you can definitely guarantee that the asserted type is correct.

III. Core Analysis: The Principle of as unknown as Double Assertion

Now that we understand the unknown type and basic assertions, let’s look at the as unknown as double assertion. Its core logic is simple: Use the “intermediate bridge” feature of the unknown type to achieve conversion between any types.

First, remember two key rules (basic conventions of TypeScript’s type system):

- Any type can be asserted as

unknown; unknowncan be asserted as any type.

Combining these two rules forms the path of “double assertion”: Type A → unknown → Type B. Through the unknown intermediate layer, we bypass TypeScript’s restriction on direct assertion between “non-parent-child types.”

Here’s the most intuitive example: Converting a number type to a string type (they are not parent-child types, so direct assertion will report an error):

let num: number = 123;

// Direct assertion: Error! TypeScript disallows direct assertion between non-parent-child types

let str1: string = num as string; // Error: Conversion of type 'number' to type 'string' may be a mistake...

// Double assertion: Successfully converted via unknown intermediate layer

let str2: string = num as unknown as string; // No error, and type checking is retained

console.log(str2.toUpperCase()); // Compiler allows calling string methods (runtime error depends on actual value)At this point, you might be wondering: Both as unknown as and as any as can achieve conversion between any types, so why is the former safer?

The key difference lies in the intermediate layer:

as any as: The intermediate layer isany, which completely disables type checking. For example, after converting anumberto astring, you can then convert it to anArray, and the compiler won’t report an error—this is extremely risky.as unknown as: The intermediate layer isunknown. While conversion is allowed, subsequent operations are still subject to type checking. For example, after converting anumbertounknown, you can’t directly calltoUpperCase; you must first assert it as astring—this adds an extra “confirmation” step, reducing the possibility of incorrect operations.

IV. Practical Scenarios: When Should You Use as unknown as?

Although as unknown as is safer than as any, it is essentially a “forced type conversion” and a “last-resort solution.” From years of project experience, I’ve summarized 3 scenarios where it’s truly necessary to use it; avoid it in all other cases.

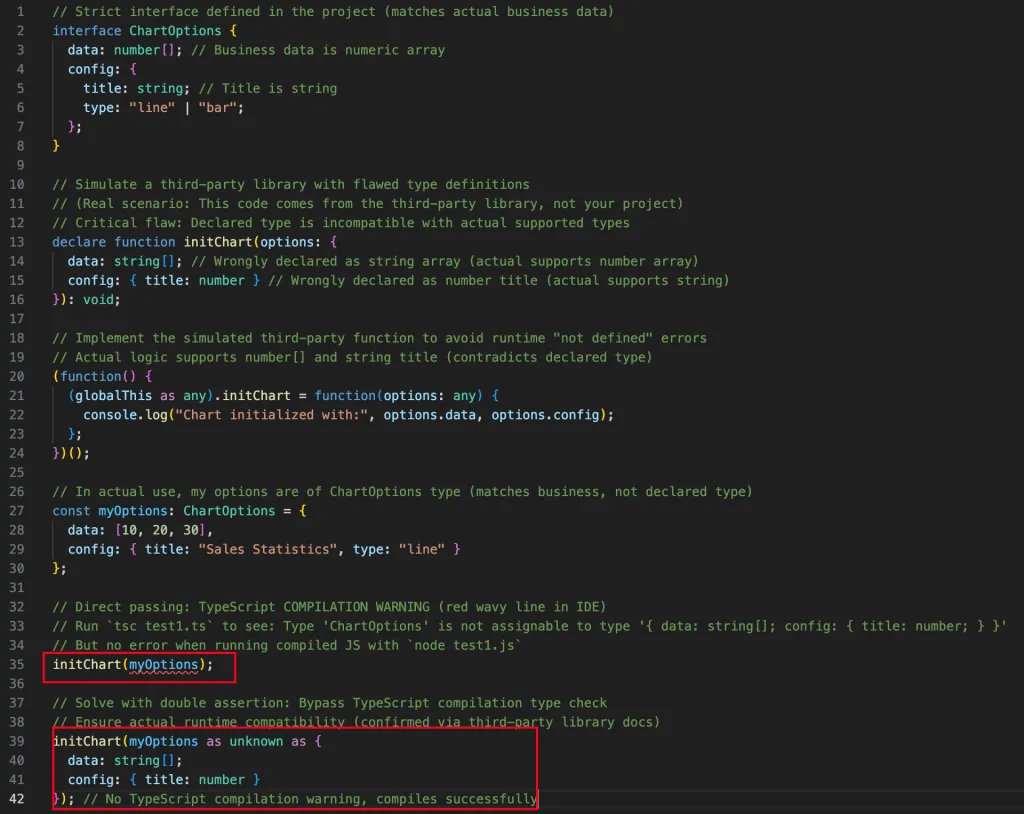

Scenario 1: Integrating Poorly Designed Third-Party Libraries

Many early third-party libraries do not provide TypeScript type definitions (or have incomplete/inaccurate type definitions), which can lead to type mismatch issues when calling the library’s methods.

It’s important to clarify: These issues occur at the TypeScript compilation check level, not the Node runtime level. Because type information is stripped when compiled to JavaScript, running directly with Node usually won’t produce warnings or errors—but this doesn’t mean the TypeScript compilation-stage type checking issue doesn’t exist.

For example, when I integrated an old chart library before, the type definition of its core method initChart was flawed: The third-party library incorrectly declared the parameter type as{data: string[]; config: {title: number} } (the data type does not match what is actually supported), but it can actually handle number[] data and string titles at runtime. In my project, I defined a ChartOptions interface that better fits the business (with data as number[] and title as a string). Directly passing this interface will explicitly trigger a type incompatibility warning at the TypeScript compilation stage (red wavy line), but compiling the code to JavaScript with tsc and running it with Node won’t report an error (since JavaScript has no type checking). This scenario—”compilation check fails, but runtime works”—is one of the applicable use cases for as unknown as: It solves the type blocking issue at the TypeScript compilation stage, not runtime errors.

Note: You need to execute TypeScript compilation via the tsc test1.ts command to see the type warning; running directly with node test1.ts essentially uses tools like ts-node to skip compilation and execute directly, so no type checking is triggered.

// Strict interface defined in the project (matches actual business data)

interface ChartOptions {data: number[]; // Business data is numeric array

config: {

title: string; // Title is string

type: "line" | "bar";

};

}

// Simulate a third-party library with flawed type definitions

// (Real scenario: This code comes from the third-party library, not your project)

// Critical flaw: Declared type is incompatible with actual supported types

declare function initChart(options: {data: string[]; // Wrongly declared as string array (actual supports number array)

config: {title: number} // Wrongly declared as number title (actual supports string)

}): void;

// Implement the simulated third-party function to avoid runtime "not defined" errors

// Actual logic supports number[] and string title (contradicts declared type)

(function() {(globalThis as any).initChart = function(options: any) {console.log("Chart initialized with:", options.data, options.config);

};

})();

// In actual use, my options are of ChartOptions type (matches business, not declared type)

const myOptions: ChartOptions = {data: [10, 20, 30],

config: {title: "Sales Statistics", type: "line"}

};

// Direct passing: TypeScript COMPILATION WARNING (red wavy line in IDE)

// Run `tsc test1.ts` to see: Type 'ChartOptions' is not assignable to type '{data: string[]; config: {title: number;} }'

// But no error when running compiled JS with `node test1.js`

initChart(myOptions);

// Solve with double assertion: Bypass TypeScript compilation type check

// Ensure actual runtime compatibility (confirmed via third-party library docs)

initChart(myOptions as unknown as {data: string[];

config: {title: number}

}); // No TypeScript compilation warning, compiles successfully

Scenario 2: Handling Complex DOM Operations or Browser APIs

While type definitions for modern browser APIs are quite comprehensive, the compiler may still fail to accurately infer types when handling special DOM elements (such as custom components or elements inside iframes).

For example, obtaining the DOM instance of a custom component in a React project:

import {useRef, useEffect} from 'react';

import CustomInput from './CustomInput';

// DOM instance type of custom component

interface CustomInputInstance {focus: () => void;

clearValue: () => void;}

function App() {

// useRef defaults to inferring type as React.RefObject<CustomInput>

const inputRef = useRef<CustomInput>(null);

useEffect(() => {

// Need to assert as CustomInputInstance to call clearValue method

if (inputRef.current) {

// Direct assertion: Error! CustomInput and CustomInputInstance are not parent-child types

(inputRef.current as CustomInputInstance).clearValue(); // Error

// Double assertion: Success

(inputRef.current as unknown as CustomInputInstance).clearValue(); // No error}

}, []);

return <CustomInput ref={inputRef} />;

}Scenario 3: Refactoring Legacy Projects (Gradual Migration to TypeScript)

When gradually migrating legacy JavaScript projects to TypeScript, you’ll encounter a lot of “type-ambiguous” code. Using as any directly will make subsequent maintenance difficult, while as unknown as can ensure the current code runs while leaving clues for subsequent type completion.

For example, there’s a global variable globalData in an old project with ambiguous type, which requires temporary assertion during migration:

// Global variable from old project (no type)

declare const globalData: any;

// Type defined in new project

interface UserData {

id: number;

name: string;

}

// Use double assertion during migration: Temporarily convert type while retaining type checking for UserData

const userData = globalData.user as unknown as UserData;

console.log(userData.id); // Compiler prompts id is number type, facilitating subsequent maintenanceV. Pitfall Avoidance Guide: 3 Core Principles for Using as unknown as

Even though as unknown as is relatively safe, it shouldn’t be overused. Based on years of project experience, I’ve summarized 3 must-follow principles to avoid pitfalls:

Principle 1: Prioritize “Type Narrowing” Over Direct Assertion

In many cases, the compiler can’t infer the type due to insufficient code context. At this point, you can solve the problem through “Type Narrowing” instead of directly using double assertion.

For example, check the type of the value before operating on it, rather than asserting directly:

// Not recommended: Direct use of double assertion

function processValue(value: unknown) {

const str = value as unknown as string;

console.log(str.length);

}

// Recommended: Type narrowing first

function processValueBetter(value: unknown) {if (typeof value === "string") {

// Compiler automatically infers string type, no assertion needed

console.log(value.length);

} else {throw new Error("value is not a string type");

}

}Principle 2: Only Use It When You “100% Confirm the Type”

The essence of double assertion is “telling the compiler you know better,” but if your judgment is wrong, a runtime error will still occur. For example, asserting a number type as a string and then calling toUpperCase will throw an error at runtime.

Therefore, you must have sufficient basis before using it—such as checking third-party library documentation, confirming the actual type of the DOM element, or reviewing the logic of old code.

Principle 3: Add Comments to Explain the Reason for Assertion

In team collaboration, directly using as unknown as can confuse other developers. It’s best to add comments at the assertion site explaining “why the assertion is needed” and “what the actual type of the current value is” to facilitate subsequent maintenance.

// Comment example: Explain the reason for assertion and actual type

const chartConfig = rawData as unknown as ChartOptions;

// Reason: rawData comes from a third-party API, the return format is consistent with ChartOptions, but there is no type definition

// Subsequent optimization: Remove this assertion after the third-party API provides type definitionVI. Summary: The Correct Positioning of as unknown as

To emphasize one last time: as unknown as is not a “best practice” but a “temporary solution.” Its core value is to solve special scenarios that cannot be resolved through normal type inference without abandoning TypeScript’s type safety.

As developers, our goal should be to minimize the use of type assertions—by improving type definitions, optimizing code structure, and reasonably using type narrowing, we can let the compiler naturally infer the correct type. Only in unavoidable situations such as integrating poorly designed third-party libraries, handling complex DOM, or refactoring legacy projects, should we consider using as unknown as and strictly follow the pitfall avoidance principles.

I hope this article helps you truly understand the principles and usage scenarios of as unknown as, rather than just remembering “this works without errors.” If you have other questions about TypeScript type assertion in actual projects, feel free to discuss them in the comments!

Extended Thinking (Welcome to Discuss)

Have you encountered scenarios where double assertion is unavoidable in your projects? Are there better solutions than as unknown as? Welcome to share your experiences!